The Food System is a fragile structure, each piece relying on multiple parts and interdependent relationships. While many of these relationships and features are mostly hidden from our view, food, and our food systems affect us every day and have a significant impact on our lives and our health, from determining what food is available on our grocery shelves to what ends up on our plates every time we sit down for a meal.

Food Systems are comprised of a web of interlocking structures that include production, aggregation, processing, distribution, access, consumption, waste, and policy.

These structures and dependencies repeat at all sizes and scales of food systems, whether it is our global food system or our Southcoast regional food system where we have over 1500 small farms.

Learning about our local food system and the larger food systems in which it is embedded, allows us to understand the pieces we don’t see every day but that play a major role in determining what we eat. Understanding the ‘hows’ and ‘whys’ of our food systems allows us to make more informed choices as consumers and actively build stronger, more resilient, and more equitable food systems and supply chains. It will enable us to manage our health, starting with the food on our plate, and support thriving and resilient local economies and agricultural communities.

The Main Components of A Food System Are:

The Production of Food (agriculture, fishing, aquaculture)

The Aggregation, Processing, and Distribution of Food (facilities that kill animals or harvest vegetables and fruit to clean, cut, package, and transport)

Access and Consumption of Food (is it affordable, is it near me, is it culturally relevant)

Food Recovery and Waste (organics rescued and moved into food relief programs, or is food composted or thrown in a landfill)

Food Policy is creating policies that support this entire system to create a healthier community and foster robust economic structures.

Starting with our domestic food system, we can see how it is both contingent on the global and international food systems as well as the driving influence on our food systems at the smallest scale.

The United States is one of the largest exporters of the globalized food system. Our exports account for roughly 20% of what farmers are producing, so while we are considered strong from a global food system perspective – we export more than we import, and our domestic market is our largest market – we still struggle with the same challenges that affect food systems worldwide and on the Southcoast. We can see how the national food system structures disadvantaged our small and local farms. It is also a global and national food system with significant waste and does not mitigate environmental degradation due to agriculture, putting our ability to continue to farm at risk.

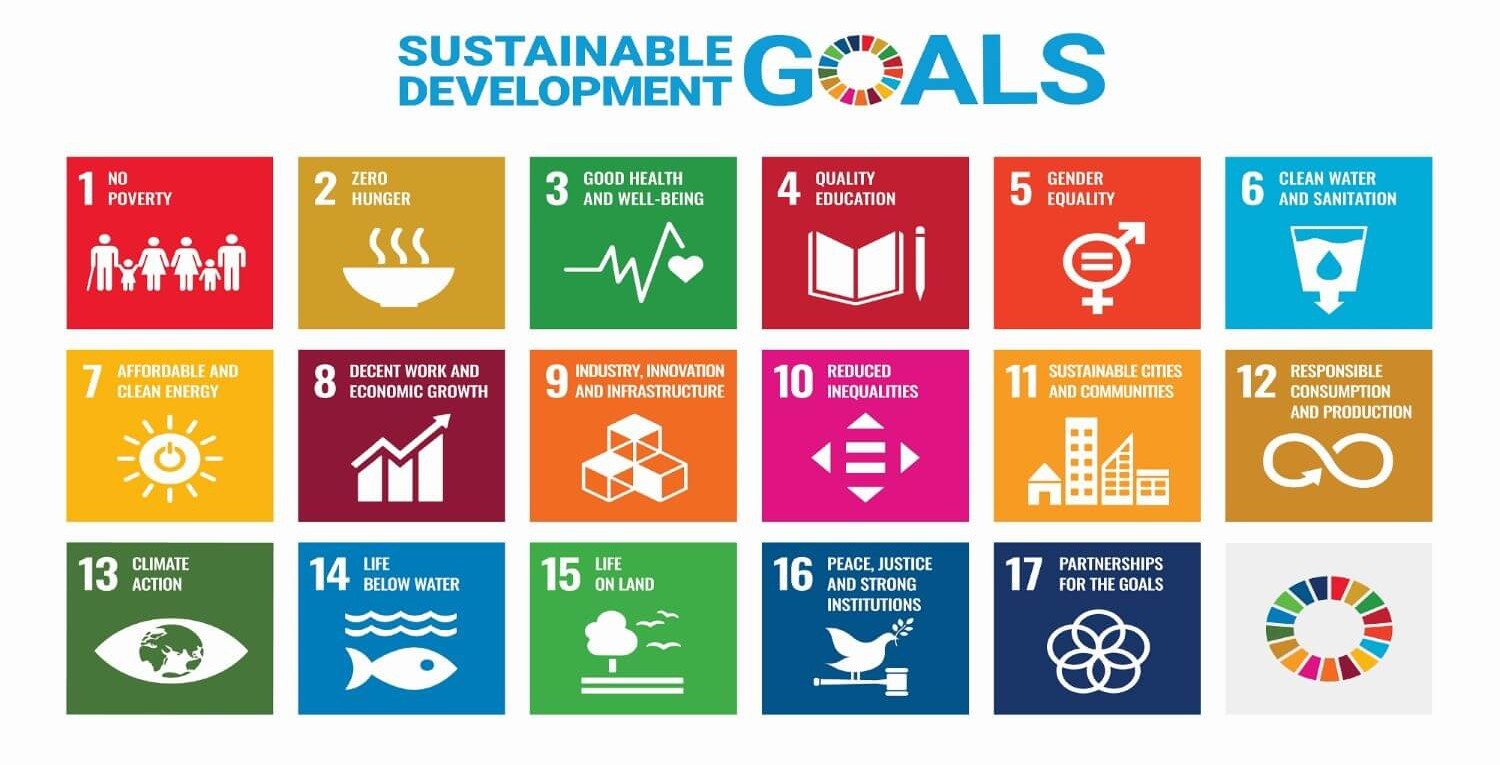

UNSDG Goal #2:

Zero Hunger

End Hunger, Achieve Food Security, and Improved Nutrition and Promote Sustainable Agriculture

In 2020, 149.2 million children worldwide under the age of five suffered from stunting due to malnourishment.

In the United States, the USDA reports that 1 in 10 households are food insecure. While levels of food insecurity have fluctuated significantly from 2020 to today, in Massachusetts, the current 2023 rate of food insecurity is measured at approximately 16-18% of households and possibly even significantly more.

UNSDG Goal #9:

Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

Build Resilient Infrastructure, Promote Inclusive and Sustainable Industrialization and Foster Innovation

The concentration of monopolies that control vegetable and fruit seeds, fishing and aquaculture, animals, transportation, and other food systems structures such as the lack of small-scale producers and distributors, lessens our ability to increase our global food supply in the face of a crisis such as COVID-19.

UNSDG Goal #12:

Responsible Consumption and Production

Ensure Sustainable Consumption and Production Patterns

The unsustainable way we have produced and consumed food has contributed to pollution, climate change, and loss of biodiversity. Earth’s resource consumption now exceeds our renewal capacity by about 30 percent. Extractable water now accounts for about 93 percent of water used for agriculture. Less biodiversity has made the food system less resilient to climate impacts. Thus, there is a greater vulnerability to climate change, new plant pests, and new diseases. Agricultural emissions can contribute up to 29% of greenhouse gases. Shifting how we farm is one of the most significant changes we can make to affect climate change. If you are not a farmer, the biggest impact you can have in positively affecting climate change is shifting the way you eat.

To understand how to apply these global initiatives at the smallest local level, we need to examine the current state of agriculture in the United States and how we got here. We can then look at each of the key components of our food system and examine the relationships and interdependencies that affect our everyday lives. Our “food system has many challenges,” and below is a preview. You can find more information by clicking the titles of each chapter: Food Production, Aggregation and Distribution of Food, Food Access and Food Consumption, Food Recovery and Food Waste, Food Policy, and How You Can Get Involved.

Food Production

Globally, we’ve seen a shift toward mono-cropping, meaning large acreage planted in a single plant variety such as corn, soybeans, wheat, and cotton, and we have seen the heavy use of fertilizers, pesticides, water, groundwater with irrigation systems, and a significant reliance on fossil fuels. According to Robert S. Lawrence, MD, from the Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health, the primary use of field corn is for animal feed, including 37 percent of field corn fed directly to the animals, cattle, swine, and chickens. Industrial seafood finds its way to our tables in two ways: wild fish that are caught in our rivers, lakes, and oceans, and farmed fish that are raised in controlled conditions. The most prominent farmed seafood in the US is shrimp and salmon. One of the challenges in the seafood industry is overfishing. Dr. Jillian Fry, PH.D., from Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health, said our fishing equipment significantly impacts the ocean. 85% of fisheries are depleted, exploited, or still in recovery.

Aggregation and Distribution of Food

Ever wondered where food goes once harvested, raised, or caught? Vegetables and fruits go to aggregators that clean the produce, separate the perfect and non-perfect items, package, label, and then transport that produce to retailers. Animals are taken to slaughter facilities, killed, cut and cleaned, packaged and labeled, frozen, and shipped to retailers. Seafood is frozen, cleaned, cut, packaged, labeled, and shipped.

Food Access and Food Consumption

We often think that the food we eat is expensive and that the food we buy from farmer’s markets is more costly than you would find in a big franchise grocery store. The truth is that we do not pay the actual cost of food in a grocery store. Grocery stores buy food from large farms, where those large farms have access to new technology and farm equipment, utilize grants and subsidies, buy seeds in bulk, and grow only one or two types of food. Local farmers often do not have access to these resources and will usually pay more to their employees and use agroecological farm practices; thus, the cost of their food may be more than what you would find in a grocery store. The true cost of food is hidden, but we see it in the degradation of the environment (ocean and land) and the large number of people in the United States that are overweight, have heart disease, diabetes, or other diet-related diseases.

Food Recovery and Food Waste

What happens after we prepare food and after we eat food? According to Roni Neff from the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, 40% of the food supply in the US ends up in landfills, producing one-quarter of the US’s harmful methane emissions. But better ways of managing our food waste exists. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has created a triangle of the hierarchy of how we deal with the back end of the food system or the Food Recovery and Food Waste process. According to the EPA, here is the order in which to handle organic waste:

- to buy and consume less

- if food is edible, then give it to the food relief organizations

- if the food is not edible, then it should go to farms so animals can eat it

- if oils in food can be used for fuel, then we use it that way

- if that is not an option, we should compost the food and put it back into the soil,

- and last, food should go to landfills for incineration.

In the Southeastern Massachusetts counties of Bristol, Norfolk, and Plymouth, we can see other impacts of the local food system in detail.

In our research from the 2021 Southcoast Food System Assessment, a survey of 490 families in 2020 showed that 39% often or sometimes worry that food will run out before there is money to buy more. 19% of people surveyed reported that if they live in an urban setting, they are over one mile from a grocery store, and if they are in a rural area, they are often over 20 miles from the grocer. While participation in the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is increasing, as of 2020, 45% of people eligible for SNAP are not receiving SNAP. In our area, restaurants and other food enterprises have been particularly hit hard during the COVID-19 pandemic, and they are struggling to fill available positions due to a national labor shortage and wage competition.

We need a resilient local food system, but what does a resilient food system mean? Resilience means that in the face of disruptions or shocks to the food structure, pieces or the entire food system adapt and grow, remain flexible, and has some capability to respond to extreme events, such as severe weather events or health pandemics. Learning about the Food System and your place in this system is critical to creating the necessary changes to ensure we all have access to nutritious, affordable, and culturally appropriate food.

Food Policy Councils like the Southcoast Food Policy Council, are organizations that pull groups together to evaluate the local food system, provide collaborative solutions, increase coordination of food resources, and advocate for the needed changes. The Southcoast Food Policy Council’s task is to look long-term and using regionally specific data and research like the 2021 Southeastern Food System Assessment, bring stakeholders together to determine priorities of initiatives that need to be implemented and policies that need to be enacted to create a healthy and robust local food system that can withstand crises and shocks such as a pandemic or climate change.

Become a Food System Citizen by learning more about our global, national, and local food systems.

By doing so, you are taking power into your own hands to determine what we eat, how we grow food, how to make food accessible and affordable, and what actions you can take to lessen climate impacts and create a future for your children and grandchildren. We encourage you to learn more by investigating the resources below and our website’s other “Know Your Local System” pages.

Resources

- The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

- Video: What are The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals

- The Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future’s online Food System learning tool: www.foodsystemprimer.org

- Neff, Roni (editor). “Introduction to the US Food System: Public Health, Environment, and Equity” Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future. 2015 Published by Jossey-Bass.

- “Introduction to the Food System” certificate from Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health

- Agriculture- Robert S. Lawrence, MD Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health)

- Fisheries: Jillian Fry, Ph.D. Johns Hopkins University, Bloomberg School of Public Health

- The 2021 Southcoast Food System Assessment

- Video: “We are all part of our food system”

- Video: “Why do we need to change the Food System?”